"Into the Night": Cornell Woolrich's art of darkness revisited

(This story originally appeared in the Asbury Park Press, Sept. 27, 1987)

He's been called "the Poe of the 20th Century" and "the greatest

suspense writer that ever lived" and yet, nearly 20 years after his death,

Cornell Woolrich in many ways remains as much a mystery as the novels he

wrote.

Widely hailed as the father of the psychological suspense tale,

Woolrich was the author of two dozen novels and more than 200 short stories

and novelettes. His haunting prose style and dark themes spawned a whole new

category of literature and though his work remains unknown to many, his

legacy has been a lasting one.

"No one can write suspense the way Woolrich did," said Prof. Francis M.

Nevins Jr., a Woolrich authority and author of the forthcoming biography

"Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die," to be published next year

by Mysterious Press. "I've read and reread everything the man wrote and he

still doesn't bore me. He did in prose what Hitchcock did in film. "

Although most of them have been out of print for many years, many of

Woolrich's early suspense stories from the 1930s and '40s take place on the

Jersey Shore.

"There are some very interesting Jersey stories that he wrote, enough to

fill a small book," Nevins said. "We don't know how often he went down there

but he seemed very interested in the Asbury Park area, it really seemed to

fascinate him. There's one classic, a very early one, called "Boy With Body'

which is set on the Jersey Shore back around 1935. That's a setting that

recurs at least half a dozen times in Woolrich's stories."

In France, where Woolrich is considered a master of his art, he is

credited with the creation of the roman noir - the "black novel" - a style

of writing that spawned the Hollywood film noir of the 1940s and '50s. More

than 30 films have been made from Woolrich's works, including such classics

as "Phantom Lady" (1946), "The Window" (1949), "The Leopard Man" (1943), and

perhaps the most famous film based on a Woolrich story, Alfred Hitchcock's

"Rear Window" (1954).

Though not as well known as the works of other noir stylists such as

Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, Woolrich's novels, many written under

the pseudonyms William Irish and George Hopley, today are regarded as

near-forgotten masterpieces of the form. With evocative titles such as "The

Black Angel," "The Night Has a Thousand Eyes" and "Waltz into Darkness,"

Woolrich's tales were charged with an undercurrent of fear, guilt, despair

and, as Nevins says, "a sense that the world is controlled by malignant

forces."

Woolrich's characters were everyday people caught up in circumstance,

often persecuted for crimes they did not commit. In "The Black Curtain"

(1941), a man recovers from a three-year bout of amnesia to find himself

being pursued by shadowy figures from a past he can't remember. In "Phantom

Lady" (1942), an innocent man is charged with murder and sentenced to death,

only to find that the one woman who can prove his innocence has vanished

without a trace.

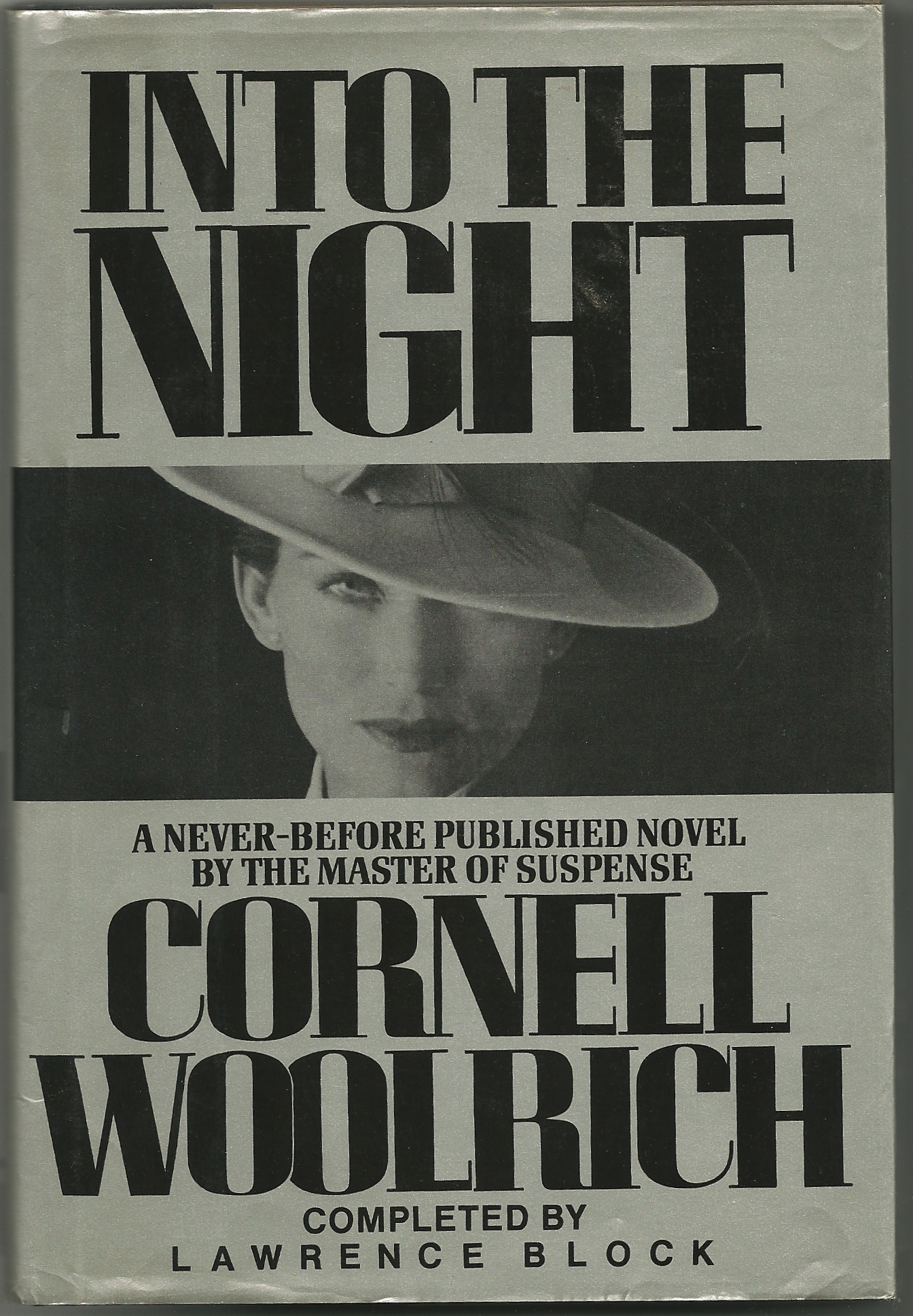

Now, nearly two decades after his death, Woolrich's art of darkness

seems to have won renewed appreciation. The majority of his major novels

from the 1940s have been reprinted in paperback by Ballantine Books, and

Mysterious Press has just published "Into the Night," an unfinished novel

found among Woolrich's papers and completed by veteran suspense writer

Lawrence Block.

Nevins, a professor of law at the University of St. Louis, has devoted

much of the last 20 years to keeping Woolrich's name alive, editing

collections of his stories, traveling around the world giving lectures and

negotiating with film and TV producers over Woolrich properties. Although he

never met him, Nevins became involved with Woolrich's work in 1970, when he

was brought in by Chase Manhattan Bank, the executors of Woolrich's will, to

act as a consultant to the estate.

"When he died he left a million dollars and a million legal problems,"

Nevins said. "There were a large bureaucracy of bankers and lawyers involved

with the estate, but I believe I'm the only one in the whole tribe that had

read Woolrich to any degree."

Woolrich's already unhappy life began to fall apart at the seams after

his mother - with whom he shared what Nevins called a "bizarre love/hate

relationship" - died in 1957. A closet homosexual, an alcoholic and

diabetic, Woolrich eventually lost a leg to gangrene after failing to seek

medical treatment for an infection. He spent his final years as a recluse,

confined to a wheelchair in his one-bedroom apartment at New York City's

Sheraton Russell Hotel. It was there that he died from a massive stroke on

Sept. 25, 1968 at the age of 65. A total of five people attended his

funeral.

"He was making $50,000 to $60,000 a year from his writing in the late

'40s but he lived a terribly lonely life," Nevins said. "He had no one he

loved, he drank too much, he had no friends. His was just a wretched life."

Among the papers found in Woolrich's apartment after his death was the

manuscript of "Into the Night." Although begun in the early 1960s when

Woolrich was already a sick man, the manuscript was written in the same

style and with many of the haunting qualities of his earlier novels. In it,

a desperately unhappy young woman attempts suicide only to accidentally kill

a passerby. Wracked with guilt, she traces the dead woman's past and becomes

a self-appointed avenger of those that wronged her.

"When I first saw the manuscript, the first 22 or 23 pages were gone, an

occasional page running throughout it was missing for whatever reason, and

the end was missing except for a couple of sheets that he had crossed

everything out of," Nevins said. "Obviously, Woolrich could not figure out

how to get that book going. He knew what had to happen but he didn't know

how to make it happen."

It was Mysterious Press publisher Otto Penzler who approached Lawrence

Block, an Edgar Award-winning author himself, with the project of completing

the book and shaping it into a publishable form.

"Most of the work was figuring out what would go on the pages, not

writing them," Block (right) said in a telephone interview from his Florida home.

"Usually when you're completing another writer's work, you're writing the

ending. What I was writing was the opening and I had to decide what that

would be in addition to writing it, because there were any number of ways

the book could have begun.

"The first thing I did was the opening sequence - about 25 pages in

manuscript," Block said. "It's interesting in that, when I began writing it,

I found that without conscious effort I was writing in a style very

different from my own and, I gather, rather like Woolrich's. But I never at

any point rewrote Woolrich's work. I felt that my job was really to do as

little as possible to make the book available in a finished, readable form.

I don't by any means regard myself as his collaborator."

Despite some initial reservations about having another author complete

Woolrich's work, Nevins is happy with the way "Into the Night" emerged.

"If the choice was to have someone else finish it or to have no one ever

see it, I'd rather have someone else finish it," he said. "Eighty or 90

percent of what you're reading is precisely as Woolrich wrote it. I think

(Block) did a tremendous job. I don't think there's a single reader who

could have told where Woolrich left off and Block began. The beginning is

very much in the Woolrich mood and vein."

Those his overly dramatic and sometimes choppy prose style has often

drawn barbs from critics who regard him as little more than a pulp novelist,

in Europe Woolrich is regarded as a major American writer in a league with

Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. The late French director Francois

Truffaut made two films based on Woolrich novels, his Hitchcock hommage "The

Bride Wore Black" and "Mississippi Mermaid," based on Woolrich's "Waltz into

Darkness."

"But it's not just the French," Nevins said. "In Italy they're crazy

about him. I've met an incredible number of Italian graduate students who

are doing advanced dissertations on Woolrich's work. In the countries of

continental Europe and also to a large extent in Japan, there is a

tremendous interest in Woolrich, not just on the popular level but more and

more on the academic level."

Before his death, Woolrich put all his literary properties into a trust

fund benefiting Columbia University, which he attended briefly in the early

1920s. Even now, royalties from Woolrich's works go into a special

scholarship fund dedicated in his mother's name.

In addition to "Into the Night," Woolrich left behind key chapters of

another unfinished novel called "The Loser" and fragments of a

highly-fictionalized autobiography entitled "The Blues of a Lifetime" when

he died. Both of these may see print in some form in the future, Nevins

said. In the meantime, the majority of Woolrich's manuscripts and papers are

at the Rare Book and Manuscript Division of Columbia University. However,

Nevins said, the originals of many of his earlier works were never located.

"We don't know what happened to the great bulk of the Woolrich

manuscripts, which shows you how little he cared for his own work," Nevins

said. "He took no care at all towards keeping them. He obviously was very

ambivalent about the quality and value of everything he did in his life."

|