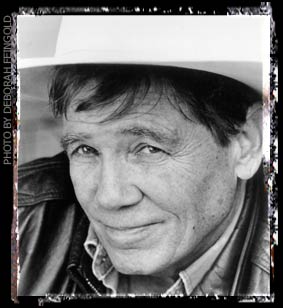

Hanging tough with James Lee Burke: Part One

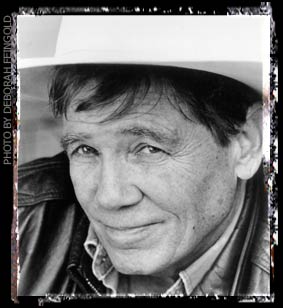

(I first interviewed James Lee Burke in 1989, shortly after the release of BLACK CHERRY BLUES, but before his Best Novel Edgar win and the subsequent attention that would come his way. At the time, Burke was teaching creative writing at Wichita State University in Wichita, Kansas. I'd read and loved HEAVEN'S PRISONERS, and after reading BLACK CHERRY BLUES, I called Burke's publicist at Little, Brown to ask if he might be available for an interview for the Asbury Park Press, where I was then working. Within minutes, my phone rang. It was Burke, calling from his office at the university, and greeting me with a hearty "Hiya, partner." At the time of this interview, Burke had just completed his fourth Dave Robicheaux novel, A MORNING FOR FLAMINGOS, which would be published the following year.)

(I first interviewed James Lee Burke in 1989, shortly after the release of BLACK CHERRY BLUES, but before his Best Novel Edgar win and the subsequent attention that would come his way. At the time, Burke was teaching creative writing at Wichita State University in Wichita, Kansas. I'd read and loved HEAVEN'S PRISONERS, and after reading BLACK CHERRY BLUES, I called Burke's publicist at Little, Brown to ask if he might be available for an interview for the Asbury Park Press, where I was then working. Within minutes, my phone rang. It was Burke, calling from his office at the university, and greeting me with a hearty "Hiya, partner." At the time of this interview, Burke had just completed his fourth Dave Robicheaux novel, A MORNING FOR FLAMINGOS, which would be published the following year.)

WALLACE STROBY: You teach full-time at Wichita State?

JAMES LEE BURKE:

Well, I teach creative writing in the fall. I have a one-semester contract. Then we go back to Montana.

We kind of bounce around a bit. My wife is a librarian and we have been fortunate enough that we were able to buy this real nice home out in this beautiful, just wonderful place. It's the most beautiful valley I've ever seen, it's just spectacular. I don't know if you've visited Montana, but, oh my heavens, it's like Rick Bass says, it's a place you associate with the afterlife (laughs).

STROBY: Are you part of that Montana literary mafia now?

BURKE: Well, I know all those guys, yeah. I've been in and out of there for 25 years. I used to teach at the University of Montana back in the '60s with Jim Crumley and Rick DiMarinis. Of course, there's a lot of other guys there, Jim Welch, the Indian writer; Tom McGuane lives up the pike; Bill Kittridge; Richard Ford; Sandra Alcosser. Man, I tell you, if you throw a rock in Montana, you'll probably knock down a writer.

STROBY: Are you from Louisiana originally?

BURKE: Yeah, that's my home. My family's from New Iberia, that's down in southwestern Louisiana on Bayou Teche, right south of Lafayette. I've been in and out of there my whole life, one way or another.

STROBY: When you go back to Montana, do you have a teaching job there too or do you write full time?

BURKE: No, I write full time. I've been pretty fortunate the last few years, I've been able to write almost every day. I've published quite a few novels in the last few years with God's good grace.

I had a lot of lean years. I published three novels in New York by the time I was 34. I published my first novel, which I wrote when I was only 23 - I finished the rewrite on it two weeks after my 24th birthday - but by the time I was 34 I had done pretty well and boy, I thought I'd arrived. I discovered I was just starting to pay dues. I hit a long period there where I couldn't sell anything. I wrote the novels - I've written several unpublished novels- but I went 13 years before LSU Press put me back between hard covers with a short story collection entitled "The Convict."

I've written four novels in a row now without a break, no interruption at all, just pulling one sheet of paper out of the carriage and putting another one in.

STROBY: Is "Morning for Flamingos" a Robicheaux novel?

BURKE: That's right, it's about Dave Robicheaux and it's set entirely in New Orleans. It deals with voodoo and black magic and Negro prostitution back in the 1950s - and fear. It's a real unusual book, but Little, Brown thinks it may be my biggest book commercially. The others have done right well in the last few years. "Black Cherry Blues" is doing real well.

STROBY: You have Cajun roots?

BURKE: Well, my family is kind of a mixture of Irish and French, I guess. I'm not a Cajun. I speak Cajun French pretty well. People in southern Louisiana are pretty mixed up, it's hard to tell what anybody is. You know the term "zydeco"? Well, see, that's a Cajun word that means "mixed vegetables" and the music is all mixed up, just like Louisiana people, it's hard to tell what anybody is. The races are mixed. There are people of color there - and that's what they call themselves - who, if you call them black, will be angry, 'cause they call themselves "Creoles." They are part Indian and part black and part French ... a lot of people in Louisiana, they're part anything that was passing through Louisiana in the last 300 years (laughs).

STROBY: Where did you go to school?

BURKE: The University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette, and the University of Missouri.

My wife and I have been married 30 years this year and we've lived all over the United States. I was a social worker on skid row in Los Angeles. I was a newspaper reporter. I drove trucks for the U. S. Forest Service. I worked in the Job Corps in the Daniel Boone National Forest in Eastern Kentucky. I worked with the Louisiana state unemployment system. I've done different kinds of work in the oil business, in the oil fields. I've taught in five colleges. I've had a pretty lousy employment history is what it comes down to (laughs). I'm a very unstable person I'm afraid.

STROBY: Did you spend any time in the military?

BURKE: Oh, you mean the stories about Dave Robicheaux? Well, his life is fiction by-and-large, but all the experiences in most of those three novels - as well as, I'd say, most of what I've written - in one way or another is kind of a synthesis of either people I've known or things out of my own experiences. Sometimes it's hard to separate one from the other.

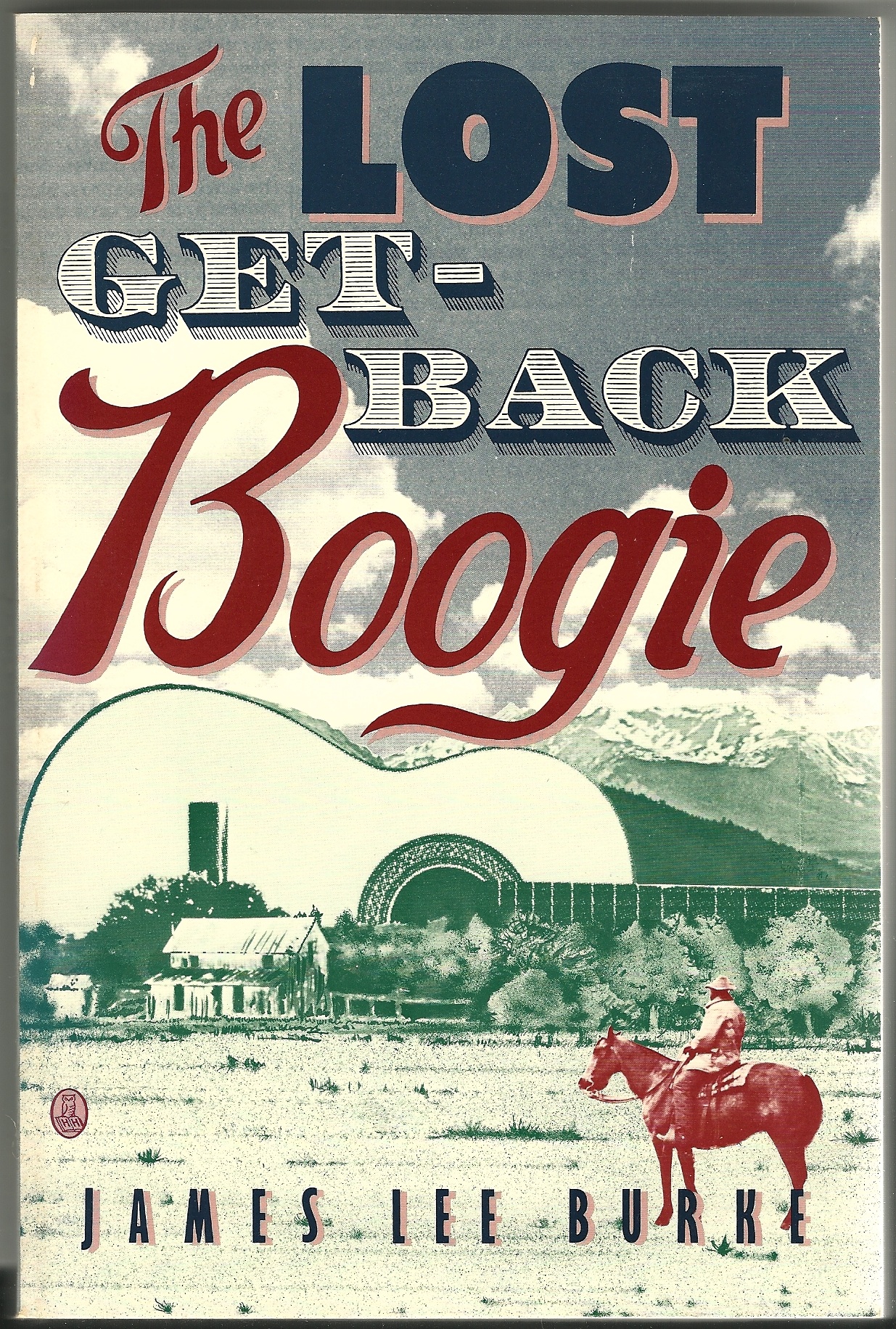

But in my novels, the autobiographical elements are such that, like most fiction, after the experience is translated into the pages of a novel it becomes hardly recognizable. Dave Robicheaux is a far better person than I. He's one of my favorite characters, however, he and a country singer I created in the novel "The Lost Get-Back Boogie" which proved to be a very successful novel.

That book had quite a story behind it. It was rejected by 52 houses in New York City. Well, it wasn't simply rejected, I mean they flung it (back) at me with a catapult. It was under submission for nine years and then LSU Press took a chance on it and it's been one of the most successful things I ever published.

I have another novel that was just reissued in trade paperback entitled "Lay Down My Sword and Shield." It's based on members of my own family, and the main character is one whom I admire very much, a guy named Hackberry Holland. But that novel had a real hard go of it. I don't know what it is . . . in the book, he becomes a lawyer for the ACLU and he's an advocate of the United Farm Workers in Texas and man, I really got trounced by some reviewers, like they were mad about something. I don't know what they were mad about, maybe they were mad at me. You know, reviewers who are mad at a character? I mean, they want to beat up a guy inside of a book?

But that book had a second run. It just was reissued by Countryman Press.

STROBY: They recently re-released a couple of Charles Willeford's early books as well.

BURKE: Oh yeah, that's how I came to know Countryman Press. I was a good friend of Charles, we worked together many years down in Miami. We both taught at Miami-Dade College. Charles and I were good friends for almost 20 years. He was a great guy, man. He was a tremendous person.

STROBY: He's sort of a writer's writer. He's someone the public doesn't know very well but writers do.

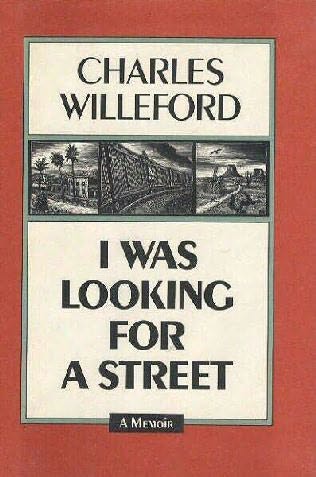

BURKE: He was very respected. You're right about that. His best work, I think, was "I Was Looking for a Street." Man, it's just such a beautifully written account about courage and hard times during the Depression. It's a masterpiece and it was virtually ignored. I'm so happy that Countryman Press brought it out. It's a terrific piece of writing.

Charles was such a fine man. He had a great sense of humor, and you're right, he was a writer's writer, a real craftsman. A guy of tremendous integrity and courage. He was so much fun to be around. And his life was an incredible story, man, it's hard to believe the things he had done.

But anyway, I owe a big debt of gratitude to a lot of people who have really invested themselves in my career. My wife and kids have been really loyal over the years, 'cause we had a lot of real hard years.

I have a wonderful agent, a guy named Philip Spitzer. Philip stuck with me through all the bad years. He's an ex-prize fighter and he was All-City New York High School basketball. He's a real rugged guy and he stands behind his clients. No agent- I told him this - no agent in New York is so self-destructive that he would submit a novel for 52 rejections. Only my agent, Philip, would hang in there that long. I dedicated "Heaven's Prisoners" to him.

And I owe a big debt to these people down at Louisiana State University Press, they put me back in business. And I have an editor named Patricia Mulcahy at Little, Brown who really put her career on the line for me. She got - on her authority alone - Little, Brown to bid $250,000 for "Black Cherry Blues." If that book went bust, she and I would both have been looking for jobs in Iran.

In other words, no one ever hears the name of the editor, all they ever see is the name of the author on the book jacket. And if I didn't have an editor who would invest so much of her own career in my work, I'd be hanging out here in left field perhaps.

STROBY: How did you get started writing? You said you wrote your first book when you were, what, 23?

BURKE: Well, yeah, I started it when I was 22 and I finished it two weeks after my 24th birthday. Are you familiar with my cousin Andre Dubus' work? Andre and I more or less grew up together - he's four months older than I, and we were always a little bit competitive, I guess, in a good way.

When I was a freshman in college and he was a sophomore, he entered a story in the Louisiana College Short Story Writing Contest, and he won First Place. Man, that was really impressive because he went to a small school in Lake Charles - McNeese State College - and he competed against entries from Tulane and LSU. So I tried it and I won an honorable mention. I was just a freshman and, man, I had been a terrible student in high school. I was dumb and I didn't go to class and I majored in wood shop and that kind of stuff. I never thought I could win an honorable mention in a state writing contest.

That same story was published in the college literary magazine. I was just 19 years old and I got hooked. I've been writing ever since. I love to write, it's the best life in the world. It's the perfect life, there's no two ways about it for me. Like Hemingway once said, it's a whole lot cheaper than psychoanalysis (laughs).

STROBY: What year would that have been that you won that contest?

BURKE: It was spring of 1956. But Andre, you see, has become maybe one of the three best short story writers in America. Some people think he is *the* best short story writer in America. But we've always kind of been pacing horses for each other.

STROBY: I noticed in one of your books you thank the National Endowment for the Arts.

BURKE: Yeah, I got a grant from them in 1977 and it cut me loose from teaching for a while and allowed me to finish this book about the Texas Revolution ("Two For Texas"). And then last year I won a Guggenheim Fellowship and, man, I owe them an enormous debt because it cut me loose for 15 months and I wrote "A Morning for Flamingos."

As I say, I was out of print for 13 years. For a long time, male writers - Southern writers - were out of fashion. The same historical currents that made Reagan a popular president also, I'm convinced, made male fiction once again popular, created a readership for it. John Wayne was back in fashion. I don't care for Ronald Reagan, I think he's a travesty. I'm not picking on the guy but the values he represents - selfishness, nationalism, mindlessness, know-nothingism, you know. The worst aspects of American life were made manifest in the last nine years and we're gonna pay for it all. The whole country went into a period of psychological denial. I think we're coming out of it, thank God. We better (laughs).

STROBY: In a couple of your Robicheaux books, and especially in "Heaven's Prisoners," you seem to tilt at making a political statement at some point, especially regarding Alafair ...

BURKE: And Central America, yeah. Well, I'm a member of Amnesty International. There are many nations in the world who are offenders against human rights and some of the worst are right here in this hemisphere. And they are the allies of the Reagan and Bush administrations, namely El Salvador, Chile, Guatemala.

Yes, my sentiments are obvious in the novels that deal with Dave Robicheaux. I have tried though, not to make the books a political treatise. But Dave does muse upon the immorality that he sees at work in the world, the political insanity.

I'm glad you bring up the question, because I use material in "The Neon Rain" which is biographical - it's not fiction - and to this day no one has ever picked up on it. I used the name of Father Stan Roether, who was a Maryknoll missionary from Oklahoma. His sister and his aunt are Catholic nuns here in Wichita. He was murdered by soldiers in this Guatemalan village where he ran an orphanage. They massacred the village, they killed 16 Indians and they killed Father Roether, and they did it with M-16 rifles and then loaded their bodies - the bodies of the Indian peasants - on a U.S. Army helicopter and flew out over the countryside and flung these bodies out at high altitudes as warning to the other Indians in the area.

These people had committed no crime. Their crime had been that leftist troops, guerrillas, had been in the village earlier. They'd come in there to buy some Pepsi-Cola or something.

But these are the allies of the Bush and Reagan Administration, there's no way around that fact. Those guns were made by the Colt Firearms Company in the United States of America.

I'm a practicing Catholic and I'll never forget listening to Alexander Haig defend the murder of those Maryknoll nuns down there in El Salvador. That guy turned my stomach, I don't know how else to put it. I thought, this is the Secretary of State ascribing the responsibility of those murders to the victims themselves. How unconscionable . . .

But this has gone on for years and years. I think we live in the greatest country on earth, by God. I'm proud of this country and I love it, and when I see it in the hands of those who are, in my mind, liars, and who arm moral imbeciles with our weapons and I simultaneously feel that no one is interested in hearing that story, it's upsetting. It has to be.

So Dave Robicheaux broods upon those things. As I say, he's a far better man than I, but he is a conscionable and moral man who is surrounded by moral imbecility. We live in an era in which, in my opinion, it's the good guys against the bad guys. I really believe that. It's a struggle for the survival of the earth. And I believe in that old civil rights song that asks "Which side are you on?" It's that simple, there's no in-between.

Robert Frost said it, that we either make decisions or decisions are made for us. There are players and there are spectators and there are too dadburn many spectators. That's kind of, I guess, a political treatise in itself. But yeah, Dave Robicheaux is concerned for those who have no advocate, who have no voice, who have no one to protect them, those who are simply voiceless, faceless and who often end up in the sights of Gatling guns.

STROBY: Which leads me to ask why a respected "mainstream" writer starts writing what could be defined as genre fiction? Did you feel you could make your points in a better way or were you just trying something completely different?

BURKE: That's a good question. Number one, as I said, I'd been out of hardback print for 13 years, and I tried everything. I published one paperback novel, a historical book about the Texas Revolution that happened to come out with Pocket Books. Then I wrote an allegory about the search for the Holy Grail. I wrote a love story set in New Iberia in 1950. I just couldn't sell anything. And I became so frustrated that . . . you hear the clock ticking when you're in your mid-40s, man. On a quiet day you can hear your liver rotting.

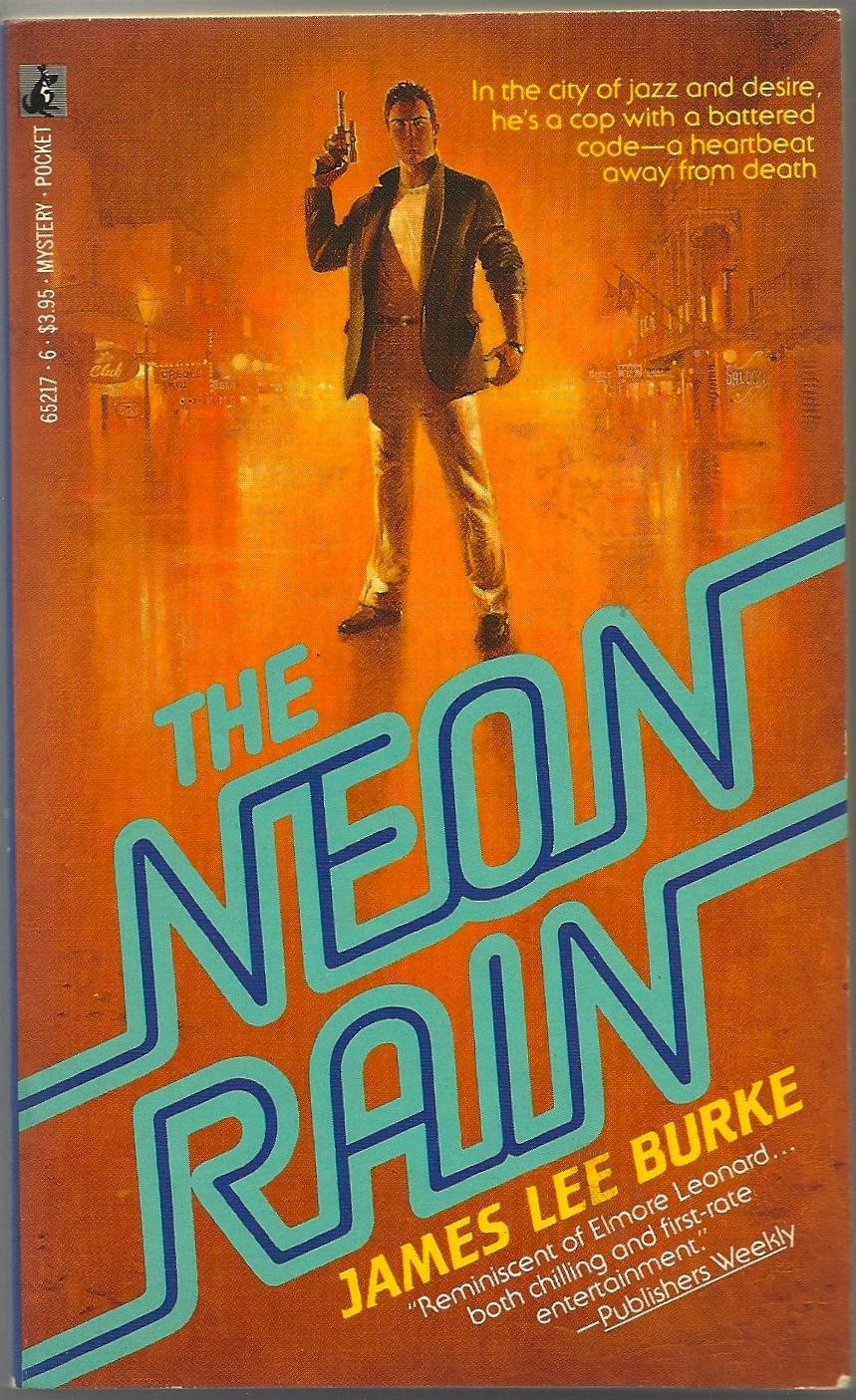

So I thought: "I'm going to try to write a literary novel within the genre." Well, at first I thought: "I'm just going to try to write a novel within the genre." I started and I wrote two chapters and I sent them to Charles Willeford down in Miami and Charles wrote me back some wonderful advice. Charles could simplify the writing process so easily. He was a very good critic and editor as well as a writer and he gave me great encouragement. I'll never forget his words, he said: "Dave Robicheaux could be a terrific character." That was the sentence that always stayed in my mind, it just kind of glowed right in the middle of his page when he wrote me that letter.

And so I finished "The Neon Rain" and I didn't know whether it was successful or not. And actually I don't know much about the genre 'cause I don't read mysteries. The only crime writer I'd ever read was Willeford, and my old friend James Crumley.

I sent it off to my agent and Philip said "Bingo." I had three offers on it right out of the box, I couldn't believe it.

I was just blown away by the success of the book. The reviews were the best I'd ever received, the book was a big seller. The paperback resale was a very good offer, it was more money than I had ever made before at writing. I was just absolutely stunned.

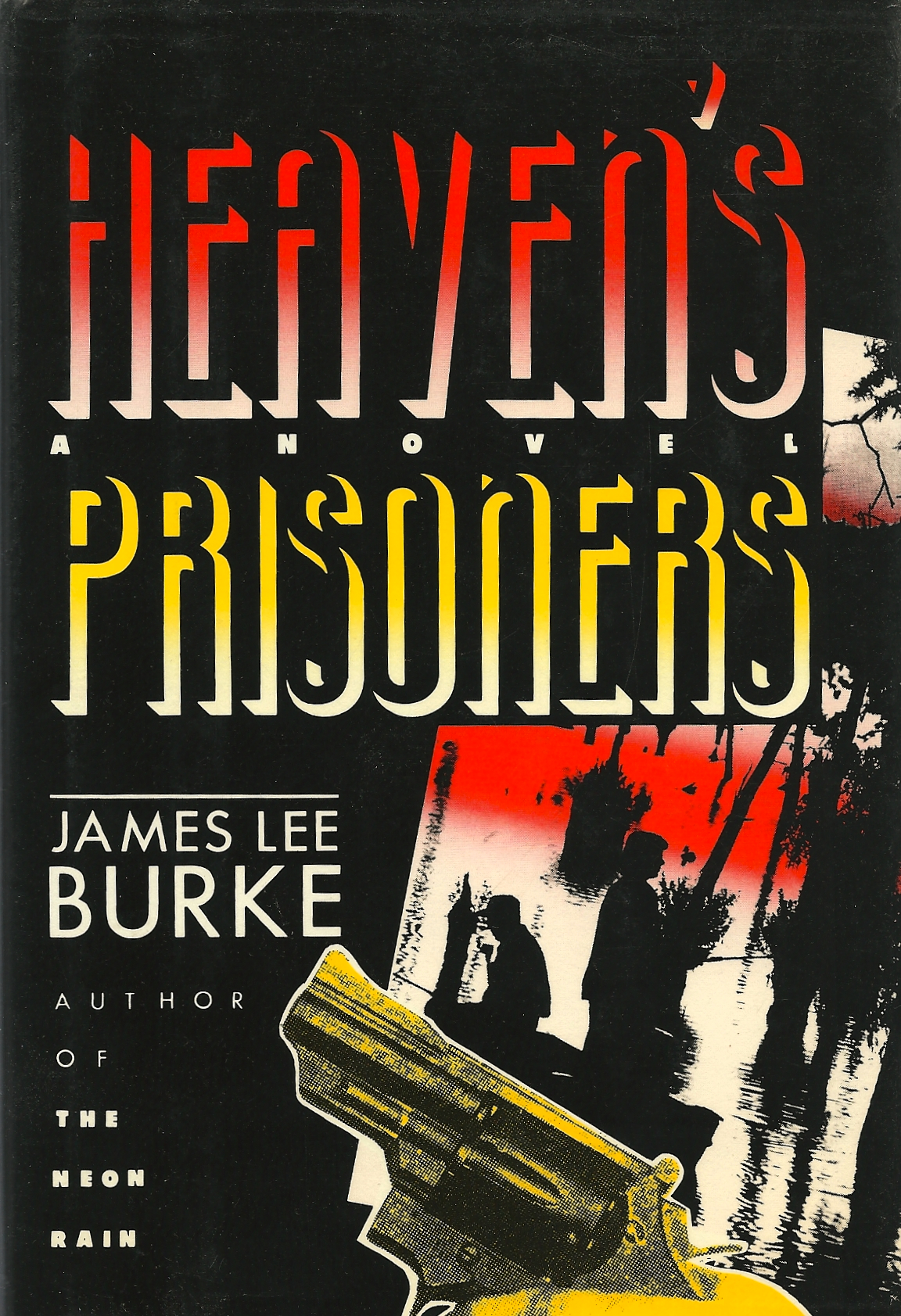

Then I wrote a second book about Dave, "Heaven's Prisoners," and like with everything I write, when I finish it I'm not sure if it works, I don't know if it's any good. I just can't see it. I mailed it to the agent and the editor simultaneously and they both called the day they received it and both used the same term - they said: "It's a masterpiece." I couldn't believe it. And "Heaven's Prisoners" was tremendously successful.

So, you know, if it all ended right now, I would be the happiest man in the world, because I never thought all this would happen. The success is just something I never would have believed. In 1985 I was virtually out of print. That was just four years ago.

STROBY: Since you jumped into the genre with both feet, are you reading more of that kind of material to see what's out there?

BURKE: Well, this is what I feel about, you know, mystery writing or crime writing, as I guess it's called. I don't know a lot about it. There are some guys that are real good.

It's like if you read Jim Crumley's book "One to Count Cadence." It's a tremendous accomplishment, one of the early novels about the Vietnam War and one of the best, probably. And Jim became quite successful with his series about a Missoula private investigator. But regardless of what Jim writes, he's ultimately an artist. He's the real article. Inside it all, there's a poet in Jim and the poet comes out his fingertips and it doesn't matter if he's writing about Vietnam or cops in Missoula, Montana.

Willeford was an artist, and that's clearly obvious in his book "I Was Looking for a Street." Charles wrote everything. He was a film writer, he wrote a book on how to raise fighting roosters, he wrote about training horses, he wrote Westerns, he wrote autobiographies. Charles wrote whatever was on his mind at the time. And he wrote it all with equal facility because he was a pro.

I think maybe the best writer in the United States today is Robert Stone, and Stone's book "Dog Soldiers" could be called a crime novel, I guess. Because it's about the drug trade, the Vietnam heroin connection. But also he's the guy who wrote "A Flag for Sunrise," which I believe is the "War and Peace" of our times. I just think that's one of the best novels I ever read.

But oftimes, people who write genre mysteries tend to be ex-newspaper people. A lot of them were police reporters at one time or another. I say this in respect to them, but I think it's a fact, many guys - and you know this from your own experience in the profession - many journalists are drawn by the ambiance of power, and they will not alienate their connection with it. There're not many police reporters who will go up against their own source. A guy quickly learns on the police beat that you go along and you get along. Otherwise they stonewall you.

In other words, their knowledge of criminality is one that is superficial at best. They see one side of the equation, they don't see it from the other side. My feeling is that a good crime novel doesn't deal with criminality, instead it deals with the nature of evil. That's the difference. How is it that we have these aberrant people among us, are they genetically defective, are they homicidal by nature, what is it in our midst that can account for this atavistic and simian creature who makes us wince? And that's what a good crime novel is about.

Elmore Leonard creates psychopathic characters who I think are quite genuine. At times I've had people tell me "these characters are too villainous." Well, check these guys out in reality, you know, meet them and find out who they are. They're not well-rounded people. They're sick, they're deviant, they're sadistic and depraved (laughs). There's no way to turn them into anything else.

STROBY: Do you find that you can address that kind of material better within the confines of a detective novel? Because after all, a detective novel, to be successful, has to have certain things. It has to have a little action, a little violence. ...

BURKE: I don't know if I'm quite following you. OK, in other words, does the action in the novel - the violence, let's say - seem an appeal to the elements that the genre reader would require for that book to be a satisfactory reading experience? Well, I hadn't thought about it in those terms. I don't think I've ever put anything in a book that I don't believe organically belonged there.

There are certain elements in any novel that are fictive devices, I guess. But actually, when the book has trouble with reviewers, it's taken to task for being a psychological and introspective novel rather than a genre one.

"Black Cherry Blues" is a mystery about the psychology of Dave Robicheaux and it operates on several levels. For that reason, sometimes genre reviewers will look at those three books about Dave Robicheaux and will find then less than satisfactory - or even objectionable - because the books don't conform to the genre. And so I have no rejoinder for that point of view. I simply write what I feel the book requires and I can say in all honesty I've never written anything into a book to make it acceptable to someone. I've got too many unpublished novels in my file as evidence of my failing to do that (laughs).

As I say, I've got those 13 years, you know, when I was really standing out in the middle of a vacant lot by myself. So it's what I've always felt about fiction, you have to write what's inside you, you have to write about what's on your mind at the time - what either makes you angry and depressed or upsets you about injustice in the world or what fills you with joy - or it won't be any good.

STROBY: That's one thing I'd noticed about your Robicheaux novels, they seem to have - if not a tone of violence, a tone of tension where you understand he's living in a very dangerous world and you're wondering where it's going to surface. But at the same time, the actual moments of the violence are few.

BURKE: Yeah. Well, I think you said it. Your definition and your observation there of what is essentially the technique in those books is absolutely correct. Hemingway once said that the most tense dialogue seems to talk about a subject which finally is irrelevant. It is what is unstated that becomes of dramatic importance. I try to do that in those books.

In other words, a violent moment, if it is to be a genuinely dramatic one in the text, has to be presented in a way that's genuine, that the effect is tragic. Because violence finally is the first option of the primitive and it is the last option of the principled. However, it indicates only one conclusion - failure on the part of civilized people - when we're violent toward one another. And we live in a very violent nation, it always has been. And particularly today.

Also, those books deal with an existentialist theme about man being alone. We live in a society in which our best efforts do not adequately confront our social problems. Nobody who's ever been a victim of crime in this country believes finally that he's invulnerable in the future. Anybody who's been there knows he's on his own. And Dave Robicheaux comes to that conclusion in "Black Cherry Blues." I believe it's quite accurate, that depiction of a victim in the aftermath of a real calamity. The person realizes he's on his own, he's a burden in somebody's caseload.

Anybody who's been there will tell you that. Maybe you have been there. But I'm sure as a newsman you have known many crime victims who just drowned, they're just absolutely destroyed psychologically because they know that in all probability nobody's going to be locked up, nobody's going to court, cops who look like Robert Redford aren't going to show up writing in their notebooks, attractive women from the prosecutor's office aren't going to take an enormous interest in the lives of the victim. That's just the way it is.

I think in New York City, four percent of the felonies that are committed are actually punished. In Miami, it's two percent. In other words, crime does pay, and people are often on their own.

STROBY: "Neon Rain" had a lot that made it very different from any other crime novel you would have found in the bookstore on the same day. But it still was very classical in some ways. Now "Heaven's Prisoners," it seems to me, was a quantum leap forward, both in terms of approach and what you were attempting to do with the novel. Would that be true? Or do you not see it as a different approach?

BURKE: No, you're right, it is. The three books are part of a trilogy that more or less was planned out from the beginning. The first book has to do with Dave making choices about life as he approaches midlife, that he no longer in effect believes in the system, he's tired of being a warden for the incorrigibles and the unteachables. He's tired of serving a system that he believes in effect is thespian and cosmetic in nature. He meets a good woman who becomes his wife, and he learns that maybe you can go back in time, back, as he says, to an era when "it was not a treason to let the season have its way." He returns to New Iberia.

But in the second book, he discovers that idyllic world that he had returned to is not immune either from the evil forces that are abroad in our land, namely narcotics. It is through a reckless choice of his own - he goes after some guys - that his wife is killed.

Now some people might fault him for the choice that he's made, but I would ask those who would criticize Dave's behavior to examine their own situation and ask of themselves what they would do. Again we're talking about a man who's confronted with danger in his own life, his family is threatened, and who discovers that the best agencies we can offer - federal or county or parish or city - are of little avail in dealing with truly evil people.

Dave kind of gets worked over sometimes by the critics as being reckless and impetuous. Well, that's fine, that's his tragic flaw. But I think it's the flaw finally of our society that oftimes the individual has to make a choice between either passivity and acceptance of his victimization, or he must become an outlaw himself.

STROBY: On that same topic, I think I see in the Robicheaux books a striving to equate what you're talking about - the forces that are out there and the fact you're all alone and no one's going to protect you - with creating a world that's decent enough to bring a child up in.

BURKE: I think so. I think you're right.

STROBY: And the contradictions inherent, that Dave has to be in some senses almost a killer to protect his world, but at the same time he wants to give his daughter a gentleness and raise her protected from that.

BURKE: Well, my feeling is that ultimately we all tend our own garden, as Voltaire told us in "Candide." And I really believe, as James Dickey suggests in "Deliverance," that much of our social apparatus is an illusion. And maybe I get that from my father, who used to say - I'll never forget his admonition to me - "Son, if everybody agrees on it, it's gotta be wrong."

And I believe that about the masses of people, God love them, but nonetheless our great nemesis is not that we are aggressive or that we're the atavistic hunter, that we're martial in spirit. We're just easily guided by demagoguing people.

But I think that ultimately each person has to create that decent environment in which to raise his children. We have four kids and thank God they've all grown up to be real good young people and we're real proud of them. But you're exactly right. It in many ways is not an easy world in which to raise kids. It's not an easy world in which they have to grow up. There's narcotics and profligate behavior and just, you know, the violence they're confronted with.

You know, I'm 53 years old, the world in which they live is not a safe one. My heavens, when I was a kid the idea of serial killers and rapists and maniacal brain-fried people who do sadistic and depraved things to innocent strangers was unthinkable. It was just something you never heard about. Maybe it happened, but I don't remember it.

But we live in an age in which hundreds of thousands of people are not simply impaired by hallucinogenic drugs or speed - I'm talking about the high level stuff that really fries a guy's electrodes - but there are hundreds of thousands of people I'm convinced who are psychotic, they're schizophrenic people running around loose in the land.

In Montana it's obvious. You know, there's no indigenous crime in Montana, except the cowboys punching each other out in the saloons. But occasionally horrible crimes happen, families are massacred, butchered alive, I mean things that are absolutely bestial. And the crimes are always committed by the same people. They're psychotic transients, usually on their way from Portland or Seattle, headed for Denver or Salt Lake. They're passing through - it's usually in the summertime - and they stop at a farmhouse and do something awful. And they all have a history of narcotic use - usually some stuff that's really bad, like acid or speed.

And I'm convinced our problems with crime are not related to poverty - that's a lot of nonsense - but it has everything to do with narcotics. We have to ask ourselves why hasn't it stopped. Well, I'm not quite sure the government wants it stopped, because it afflicts minorities and they're kept dependent and debilitated.

But I don't buy that the United States government - Bush and Reagan and these guys - are serious about cleaning up (the drug problem). It can be stopped, anything can be stopped. We fought a war in two theaters in World War II. We beat the Japanese and the Germans, and we were flat on our butts in the beginning of 1942. Nobody can tell me we can't deal with a country like Colombia, for heaven's sakes.

The United States has changed a lot since World War II. We've accomplished a lot of good things in civil rights, but we've made some hard left turns too.

STROBY: To get back to the books, how far do you see yourself going down the road with Robicheaux?

BURKE: Well, one's coming out next fall, "Morning for Flamingos." I don't know after that. But I think of it this way, Dave Robicheaux is the best character I think I've created and like any good character he has a life of his own. He'll probably tell me what he should do after awhile, the way I figure it (laughs).

NOTE: In Part Two, Burke talks about success, persistence, alcoholism and losing The Gift.

Copyright 2006 - Wallace Stroby - All Rights Reserved

(I first interviewed James Lee Burke in 1989, shortly after the release of BLACK CHERRY BLUES, but before his Best Novel Edgar win and the subsequent attention that would come his way. At the time, Burke was teaching creative writing at Wichita State University in Wichita, Kansas. I'd read and loved HEAVEN'S PRISONERS, and after reading BLACK CHERRY BLUES, I called Burke's publicist at Little, Brown to ask if he might be available for an interview for the Asbury Park Press, where I was then working. Within minutes, my phone rang. It was Burke, calling from his office at the university, and greeting me with a hearty "Hiya, partner." At the time of this interview, Burke had just completed his fourth Dave Robicheaux novel, A MORNING FOR FLAMINGOS, which would be published the following year.)

(I first interviewed James Lee Burke in 1989, shortly after the release of BLACK CHERRY BLUES, but before his Best Novel Edgar win and the subsequent attention that would come his way. At the time, Burke was teaching creative writing at Wichita State University in Wichita, Kansas. I'd read and loved HEAVEN'S PRISONERS, and after reading BLACK CHERRY BLUES, I called Burke's publicist at Little, Brown to ask if he might be available for an interview for the Asbury Park Press, where I was then working. Within minutes, my phone rang. It was Burke, calling from his office at the university, and greeting me with a hearty "Hiya, partner." At the time of this interview, Burke had just completed his fourth Dave Robicheaux novel, A MORNING FOR FLAMINGOS, which would be published the following year.)