The Great American Mystery Writer

The Great American Mystery Writer

(This essay originally appeared in the Star-Ledger of Newark, June 12, 2001)

When Samuel Dashiell Hammett died of lung cancer Jan. 10, 1961, at age 66, he was a broken man. The architect of the modern American crime novel and the author of five classic works, Hammett was nearly penniless at the time of his death, his income attached by the Internal Revenue Service, his health destroyed by a six-month stint in federal prison. It was an ignoble ending to a uniquely American life.

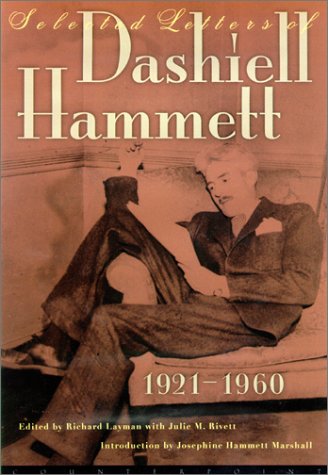

Hammett has been the subject of nearly a dozen biographies,

but none of them brings us as close to the man as the new "Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett: 1921-1960" (Counterpoint Press, $40), edited by Richard Layman (author of the 1981 Hammett biography "Shadow Man") and Hammett's granddaughter, Julie M. Rivett.

Hammett's fiction was rooted in experience. A former operative with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, he turned his talents to writing in 1922. Plagued by tuberculosis and attempting to support a wife and two young daughters, he churned out detective stories for the pulp magazines of the day, most notably Black Mask, which serialized his first two novels, "Red Harvest" and "The Dain Curse."

It was his third book, 1930's "The Maltese Falcon," that

revolutionized the genre. Hailed as the first literary crime novel, it

married Hammett's spare, muscular prose to a compelling story line populated with unforgettable characters, and at the same time addressed questions of fate and faithfulness, corruption and loyalty.

As his correspondence shows, Hammett had his own problems with faithfulness. After he separated from his wife and daughters for medical reasons in 1926 (doctors feared his worsening tuberculosis would infect his daughters), he began a long string of affairs with other women, culminating in his 30-year relationship with playwright Lillian Hellman, which lasted until his death.

As skilled as he was at writing and chasing women, Hammett seemed equally adept at pursuing his own destruction. Despite his fragile health, he smoked and drank heavily and was prone to alcoholic blackouts. As he grew older, he wrote less and drank more until, finally, he wrote not at all.

It was this inattention to his art that is the real tragedy of Hammett's life, and it is underscored in these letters. After delivering "Falcon" in June 1929, he wrote to an editor at Knopf to ask: "How soon will you want, or can you use, another book? I've quite a flock of them outlined or begun."

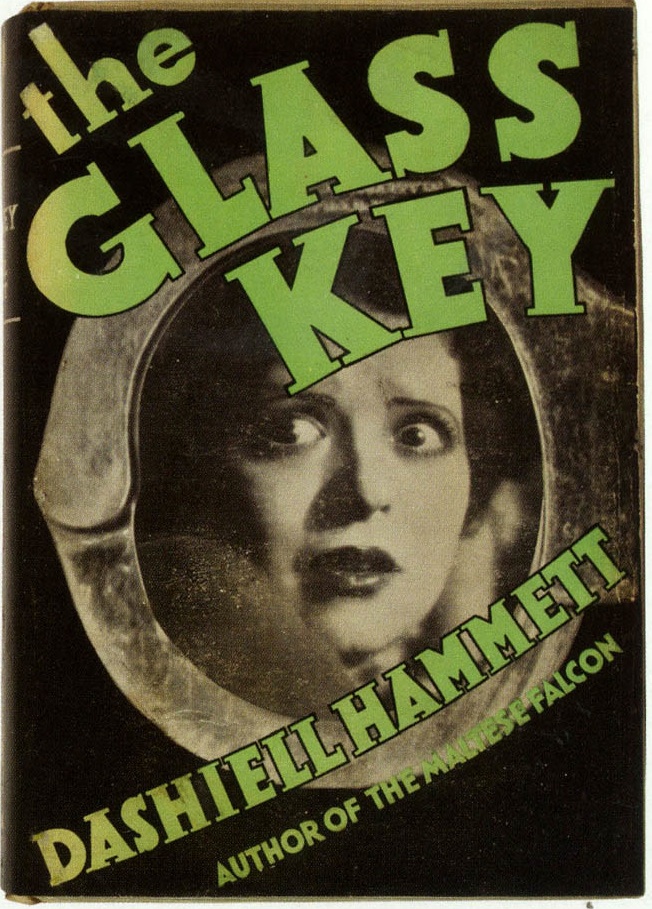

In reality, he had only two books left in him, his 1931 masterwork "The Glass Key" and 1933's "The Thin Man," a short work padded out (barely) to novel length. In his letters, Hammett makes reference to dozens of novels in progress, books with titles such as "The Secret Emperor," "Dead Man's Friday," "Toward Z" and "The Valley Sheep," all unfinished - or more likely never begun.

Knowing these details, it is easy to dismiss Hammett as an irresponsible alcoholic. But his letters tell a different story. He continued to correspond with and support his wife (they were never legally divorced) and daughters over the years. His letters to them, filled with affection, emotion and self-mocking humor, are interspersed with letters to Hellman and other lovers.

Like many artists and writers who came of age in the Great Depression, Hammett was a supporter of the American Communist Party and an unapologetic Marxist. But he also took his patriotism very seriously. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Army again (he'd served in World War I) at the age of 45 and spent most of World War II at remote outposts in the Aleutians. His reasons for re-enlisting were simple. "We're in for a long, tough fight," he wrote daughter Mary. "And anybody who can help ought to."

But Hammett's political inclinations would eventually spell his doom. In July 1951, he was subpoenaed to testify about the bail fund of the Civil

Rights Congress of New York, of which he was a member. When he refused, he was sentenced to six months in federal prison for contempt of court. By the time he was released, at age 57, his health was irreparably damaged.

Afterward, the House Un-American Activities Committee and like-minded groups continued to hound him. The IRS pursued him with a vengeance, eventually attaching all his income and passing a judgment against him for nearly $150,000 in back taxes, allegedly accrued during his years in the Aleutians.

The question of why Hammett stopped writing may never be answered, but these letters offer clues to the mystery. In 1945, he wrote to Mary about his current novel-in-progress, saying, "It's at that nice stage now when I've got nothing to do but fool around with notions and feelings and don't yet have to commit myself to anything by putting it down on paper." Eight years later, he wrote to his daughter Josephine about yet another unfinished book: "Not working on it is partly a sort of stage fright, I think ... putting the finishing touches on a book can be kind of frightening because that's that then."

Every other facet of Hammett's life recounted here - his numerous

affairs, his drinking, the Army, his social activism, the letters themselves -

seems to have served a single purpose. When he was participating in them, he wasn't writing. And they often were, to him, justifiable excuses for not writing.

Few as they are, his five books and their influence endure. All serious American crime novelists, from Chandler to Spillane to Leonard to

Ellroy, are Hammett's children. When "The Maltese Falcon" was first published, the New York Herald Tribune's reviewer predicted: "It would not

surprise us one whit if Mr. Hammett should turn out to be the Great American Mystery Writer."

Forty years after Hammett's death, it's clearer than ever. He was.